When I decided to do the Artist of the Month project, Berthe Morisot was one of the first artists I thought of. Her talents as an artist could have easily been tempered by the male-dominated art world and societal norms of her time, but she was in a unique position to contribute to the rise of the one the most recognizable and well-known art movements – Impressionism.

What is Impressionism?

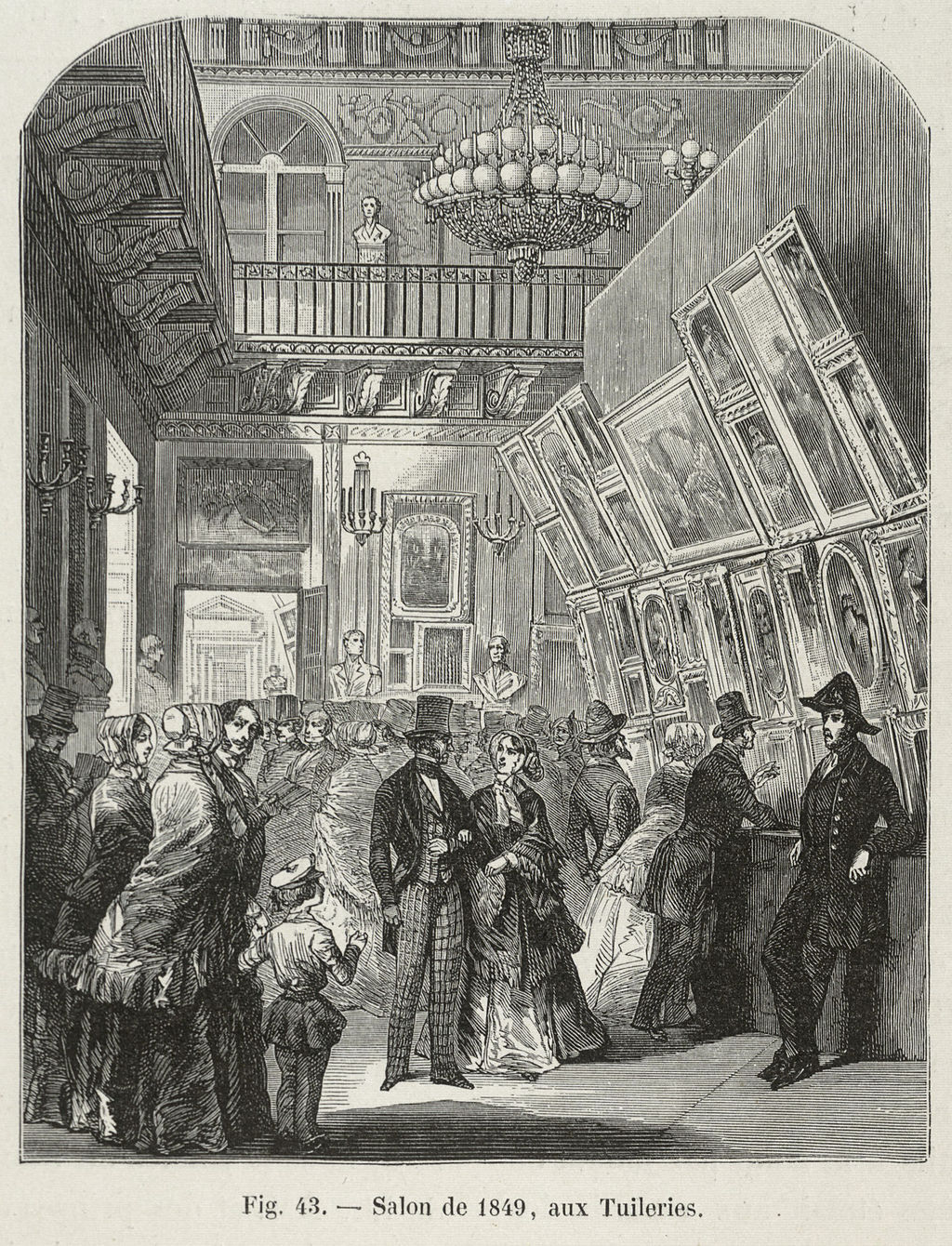

The founding members of Impressionism are names most of us know – Monet, Degas, and Pissarro to name a few. Although their individual styles varied, as a group their work rejected the established styles typically shown at the annual Salon de Paris. (The Salon was an exhibition that was considered to be essential to the success of an artist.) From its beginnings in the 1860s, Impressionism brought new ideas, genres, and advancements in the art world.

The style is comprised of loose brushstrokes, described by conservative critics of the time as sketchy and unfinished. Others saw it as a modern take, noting the bright, unblended colors that stood in contrast to the more traditional contemporary works seen at the Salon. Shadows were rendered in color rather than neutrals, and old yellow varnishes were traded in for unvarnished works that allowed newer, brighter colors to shine.

This new way of painting also changed the way the subject matter was viewed. Earlier works were carefully composed, static images. Impressionist pieces captured a moment, as fleeting as each brushstroke that created the composition. The subject matter itself was also different. Where contemporary pieces were often religious-themed, Impressionism depicted everyday life and traded the controlled environment of the art studio for plein air (open air, or outside) painting.

By Theodor Josef Hubert Hoffbauer – This image is available from the Brown University Library under the digital ID 1189455725390625., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24755293

Berthe Morisot’s Early Life

Berthe Morisot was born on January 14, 1841. Her father was a wealthy civil servant and her mother was related to the well-known Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Morisot and her sister Edma showed a talent for painting and studied at the Louvre under painter Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (women were not allowed to pursue a formal arts education). Although Edna gave up her artistic ambitions to marry a naval officer, Berthe continued to paint. She met Édouard Manet during her studies at the Louvre and they formed a lasting friendship.

As a result, she was uniquely positioned to pursue her art career. She was not able to frequent the cafes and studios where male artists could congregate and exchange ideas because women’s roles in society were so strictly defined. However, her friendship with Manet and eventual marriage to his brother Eugène gave her access to the art world and connections with other artists that most women didn’t have. She became friends with some of the major players of the Impressionist movement including Renoir, Degas, Pissarro, and Monet.

Berthe Morisot With a Bouquet of Violets. Edouard Manet. 1872.

What Set Berthe Morisot Apart?

It wouldn’t be fair to reduce Morisot to her status and connections. She was a talented artist that went under-recognized even until the last few years. Much has already been written on how gender and society shaped her career and how it’s been perceived over the years. Honestly, I don’t think I’ll do it the justice it deserves in this little blog post. Rather, let’s look at the work itself.

Under the tutelage of Corot, Morisot learned to paint landscapes and earned herself a spot in the Salon starting in 1864. Despite having this prestige for the following decade, she ended up destroying many of her works dating before 1869. (If trashing old work isn’t relatable as an artist, I don’t know what is.)

The Mother and Sister of the Artist. Berthe Morisot. ca. 1869

In 1874, Morisot participated in the first independent Impressionist show along with Degas, Renoir, and Monet. By this time her work had become looser, with the short, quick brushstrokes that came to define the style. The show was described by a critic as consisting of “five or six lunatics of which one is a woman…whose feminine grace is maintained amid the outpourings of a delirious mind.” She would go on to show at the Impressionist exhibition every year, except for the year her daughter was born, for the rest of her life.

Hanging the Laundry out to Dry. Berthe Morisot. 1875. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C., online collection, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3732827

Subject and Style

Female artists of the time tended to paint depictions of what they had access to – daily life. Women were not allowed to work from models in studios as men did. Berthe Morisot was no exception. While this was limiting, the female point of view offered an intimate look into the domestic lives of women. Whether it was a mother cradling her child, women taking tea, or a girl brushing her hair – the Impressionist viewpoint such personal scenes was the perfect application to capture the moment. It implies the movement of the sip of tea or a twinkle in the eye, sometimes with a single stroke of color.

Morisot was particularly talented at capturing energy of the fleeting moment, where the thick strokes of paint create additional depth with their texture, still appearing wet – something that can only be appreciated in real life.

Woman at her Toilette. Berthe Morisot. 1875-1880.

Over the course of her career, Morisot worked with oil, watercolor, and pastels. Her start was in drawing and she gravitated back to it later in her career, experimenting with colored pencils and charcoal. Her work as a whole also began to take on some of the definition seen in her early work. In 1894 she painted a striking portrait of her daughter Julie that stands in stark contrast to the loose brushwork of her other paintings. The definition of the young woman’s face is made all the more apparent by the simple background.

Julie Daydreaming. Berthe Morisot. 1894.

There’s no way to know what direction Berthe Morisot’s work would have taken next. She passed away on March 2, 1895 at the age of 54. It would be over 100 years before the public would begin to truly recognize her contributions to the art world, and even now she is still written about as a “female artist” rather than simply an artist. While the impact society had on her progress as an artist cannot be ignored, the truth is that even critics of her time acknowledged her work as being better than her peers.

Sources:

https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/berthe-morisot-who-is-she-why-is-she-important-1234581283/

https://www.biography.com/artist/berthe-morisot

Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. https://www.amazon.com/Women-Art-Society-World/dp/050020456X/